Innovation Lessons From Nature And Evolution

"...From so simple a beginning endless forms most beautiful and most wonderful have been, and are being, evolved.” - Charles Darwin, The Origins Of Species

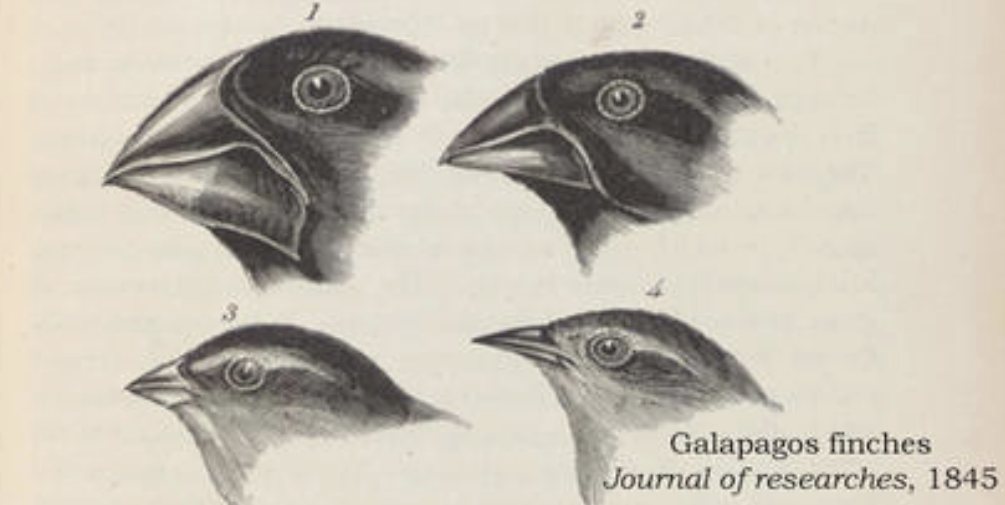

The ongoing story of the adaption of life on earth to the natural environments of our planet is nothing short of astonishing. Evolution is the most remarkable of innovators. It strikes me there is surely some level of inspiration we might take from the theory of evolution by natural selection that we can apply to our own much more prosaic and humble attempts to be innovative. Let me start out with the disclaimer that I am no biologist or expert on Charles Darwin's theory. So I apologise in advance if I use the term 'genus' when I should use 'species' or don't properly communicate the finer points of gene mutation theory accurately.

Be Open To Random

A core component of the process of evolution is the idea of random mutation. Inherited traits are passed from one generation to the next, but each new generation has new elements in its genetic makeup based on random mutation. Luck and chance play a key role in evolution, not unlike the role they have played throughout the history of science in the development of new ideas from penicillin to gravity. In contrast some approaches to innovation within organisations are so prescribed and process-led with their stage-gates, concept templates, formulaic approaches to insight and batteries of testing that they leave little opportunity for luck, chance or random events to play a role.

But there is clearly a place for the random, unplanned stroke of inspiration and it is something we should be open to. The unlikely world of stock cubes has been a recent source of a master-stroke of quite random inspiration. Oxo was one of the early pioneers of the stock cube in 1910 and then nothing much changes about them for over a hundred years. That is, until a food technician at Knorr (part of Unilever) was munching through a 'Mozart Ball' and somehow wondered whether it would be possible to create a stock ball with a shell on the outside and a soft gel-like centre that would dissolve more completely in hot water than cubes, which always seem to leave a crusty and salty residue behind.

The answer initially was no - well, at least not a stock ball with a hard outer shell (which proved resistant to dissolving in water). But the team persisted. The idea for an outer shell was discarded and the team focused instead on, quite literally, the core of the idea - the soft gel-like centre which as it turned out didn't require a shell at all. Soon afterwards Knorr Stock Gel was born. A pure stock gel stored in a small single serve tub with a brilliant flavour that was much more like real stock. This simple quite random idea has since produced hundreds of millions of dollars in revenue and inspired a generation of new products that are selling all around the world. All from a humble Mozart ball that cost less than one Euro.

Master the Art of Exaptation

In biology, "exaptation" refers to the process where a trait originally evolved for one purpose is co-opted for an entirely different one—the most famous example being feathers, which likely evolved for thermal insulation long before they ever enabled flight. In the world of innovation, this is the strategic pivot. It is the realisation that a "failed" project or a secondary feature actually possesses a hidden, more powerful utility in a different context. Slack was famously an internal chat tool for a struggling gaming company before it became a communication giant; the Post-it Note was the result of a "failed" attempt to create a super-strong adhesive. Exaptation teaches us that innovation isn’t always about inventing something from scratch; often, it’s about having the vision to repurpose an existing "mutation" for a more positive environment. It requires the humility to abandon your original intent and embrace the unexpected opportunity.

Don't Fear Cannibalisation

Evolution is not afraid of cannibalisation. New life forms and new species that are better adapted to an environment can and do overtake the old. This is the essence of natural selection. Ruthlessly and unsympathetically the old and the weak are pruned away.

An argument you often hear to justify holding back innovation or not investing in new ideas is that it will cannibalise the existing business and dilute margins. I have heard this line of thinking a lot from people in organisations. I suppose it's fine until someone else beats you to market with the idea and the cannibalisation is done by someone else rather than you. That's just called being eaten. The cautionary tale of Kodak makes this point quite well. According to an article in the Australian Financial Review earlier this year, Steve Sasson, a 26-year-old engineer at Kodak presented a prototype digital camera to company management in 1975. It drew a tepid response at best. Perhaps not in small part because of concerns it would affect Kodak's virtual monopoly of the highly profitable traditional film business. The idea was never made a priority, at least not at Kodak.

There may be times when it makes sense to hold back an idea in the interests of the broader business, but you'd be a brave CIO or CMO to bank on this for long.

Be Wary Of Unconscious Bias

Evolution doesn't apply a set of pre-conceived values or notions about what will be successful. It is value-neutral, free from confirmation bias and absent dogma. It doesn't have a dominant paradigm through which it views what it takes to succeed that creates blind spots to new forms.

It seems striking that so many of the brilliant and successful innovation ideas in the world today come from outside the dominant players in an industry and especially from startups. How can it be that IBM didn't identify the opportunity in software? That Microsoft failed to capitalise early enough on the possibilities of search? That Google overlooked social media? And that Facebook didn't see the potential of a pure photo and video-sharing play online (and had to buy Instagram instead).

Even more striking is the blind spot capitalised on by Fever Tree in the tonic and mixer market. Without wanting to downplay what is obviously a stunningly successful commercial achievement, the Fever Tree business is based on nothing more complicated than spotting a gap in the market for a more premium brand of tonic with no artificial preservatives, sweeteners or flavouring. The founders, Charles Rolls and Chief Executive Tim Warrillow, recently offloaded a 2.6% holding for over $US 100 million. And what of the stunning success of Afterpay, now with a valuation in the billions of dollars. It wasn't MasterCard, Visa, Amex or a banking giant that identified the potential for this idea despite the millions these organisations must spend each year on new product development. Innovation blind spots produced by unconscious bias are everywhere.

This is all great news if you're a startup or entrepreneur looking to innovate, but rather less good if you're in a large organisation. I wonder if the best one can do is to be aware of the possibility of bias limiting options and possibilities and to try and work from there.

Avoid Incrementalism (Unless You Have A Lot Of Time)

Evolution has been successful by effecting millions and millions of small changes over time. It also has the luxury of being able to weave its magic combination of inherited characteristics, mutation and natural selection over a very long time stretching back millions of years. Unless you have a very long timeframe indeed incremental thinking about innovation can easily be frustrating.

A lot of new business pipelines I have seen within organisations seem fully loaded with ideas and initiatives, but when you scratch beneath the surface of the charts it soon becomes obvious that a lot of the changes are minor line extensions, new varieties with slightly improved flavours or small improvements on an existing idea. Sure, it is often safer to build on what works. But such approaches rarely produce the kind of disruptive innovation that leads to dramatic growth. In the case of fast-moving consumer goods, the incremental innovation is often just a way of protecting shelf space or keeping the retail customer happy.

The wine industry produces hundreds of incrementally different wines from existing brands year after year, but a star performer in recent times has been a radically different new brand called 19 Crimes from Treasury Wine Estates. Although the wine itself is not that different (initially Australian shiraz, cabernet sauvignon or chardonnay), it's marketing and branding is breaking new ground in the wine category with a rebellious identity, use of virtual reality on the wine label and clever storytelling targeted to the millennial consumer.

By being willing to look beyond incremental innovation Treasury Wine Estates has hit upon an innovation idea that is now driving tremendous growth in a US market that has recently not been favourable for Australian wine.

Test Ideas In The Real World

Evolution doesn't have a testing laboratory. It tends to get its 'prototypes' into the real world pretty quickly where they either survive and thrive or fail. Natural selection is rather brutal in this regard.

Clearly a certain amount of rigour and robust work needs to be done to shape and refine an idea so it has the best chance of success, but there is nothing like learning from the real world performance of the product - not just whether it lives or dies, but also how to enhance and improve it over time. Silicon Valley, and Google in particular, are famous for championing this approach of launching beta versions of new software and learning from them in a safe and controlled way.

Too often million-dollar launch budgets are put behind products that ultimately fail, when some judicious in-market testing (rather than flawed market research) would have revealed fatal flaws a lot sooner. New Coke and Coors Sparkling water come rather scarily to mind. So, if you have an interesting new idea, try it, get it into market, see what consumers think, start a pop-up store. There are lots of ways to get invaluable real-world feedback early on.

Encourage A Diversity Of Solutions

Evolution keeps its options open by encouraging a diversity of forms. There is extraordinary diversity both within and between species. This diversity of natural forms is especially important for ensuring adaptation during rapid environmental change.

Rapid environmental change is what we are experiencing now right across the business landscape. Our age of technology disruption is causing all manor of shifts in culture, markets and behaviour. So when developing innovation ideas, especially early in the process, it makes sense to at least keep your options open and not narrow down too quickly.

According to Nicklas Hed of Rovio, when the company was looking for a idea to launch their foray into independent game development they reviewed several hundred ideas over many months from the development team until Jaako Iisalo, a game designer "pitched a cartoon showing a flock of birds, trudging along the ground, moving towards a pile of coloured bricks. They looked cross....but it was magical". Angry Birds was born. The business was at this point on the verge of bankruptcy but they kept their options open and resisted narrowing down on a second rate idea early in the process.

Avoid The Trap of Convergent Evolution

In nature, we often see "convergent evolution," where completely unrelated species develop remarkably similar traits—like the wings of a bird and the wings of a bat—because they are responding to the same environmental pressures. In the corporate ecosystem, a similar phenomenon occurs, but it is driven by a lack of imagination rather than biological necessity. When every organization uses the same "best practice" templates, the same rigid stage-gate processes, and the same research platforms, they inevitably converge on the same "safe" solutions. While this convergence might offer a temporary sense of security, it is a strategic dead end. True innovation requires "divergent evolution"—the willingness to ignore the common industry pressures and evolve a trait that is genuinely unique. If you follow the same map as your competitors, don't be surprised when you all end up at the same unremarkable destination.

Evolution certainly has a remarkable track record when it comes to innovation, and even if we can't match its lofty standards, we can at least learn a thing or two from its example.